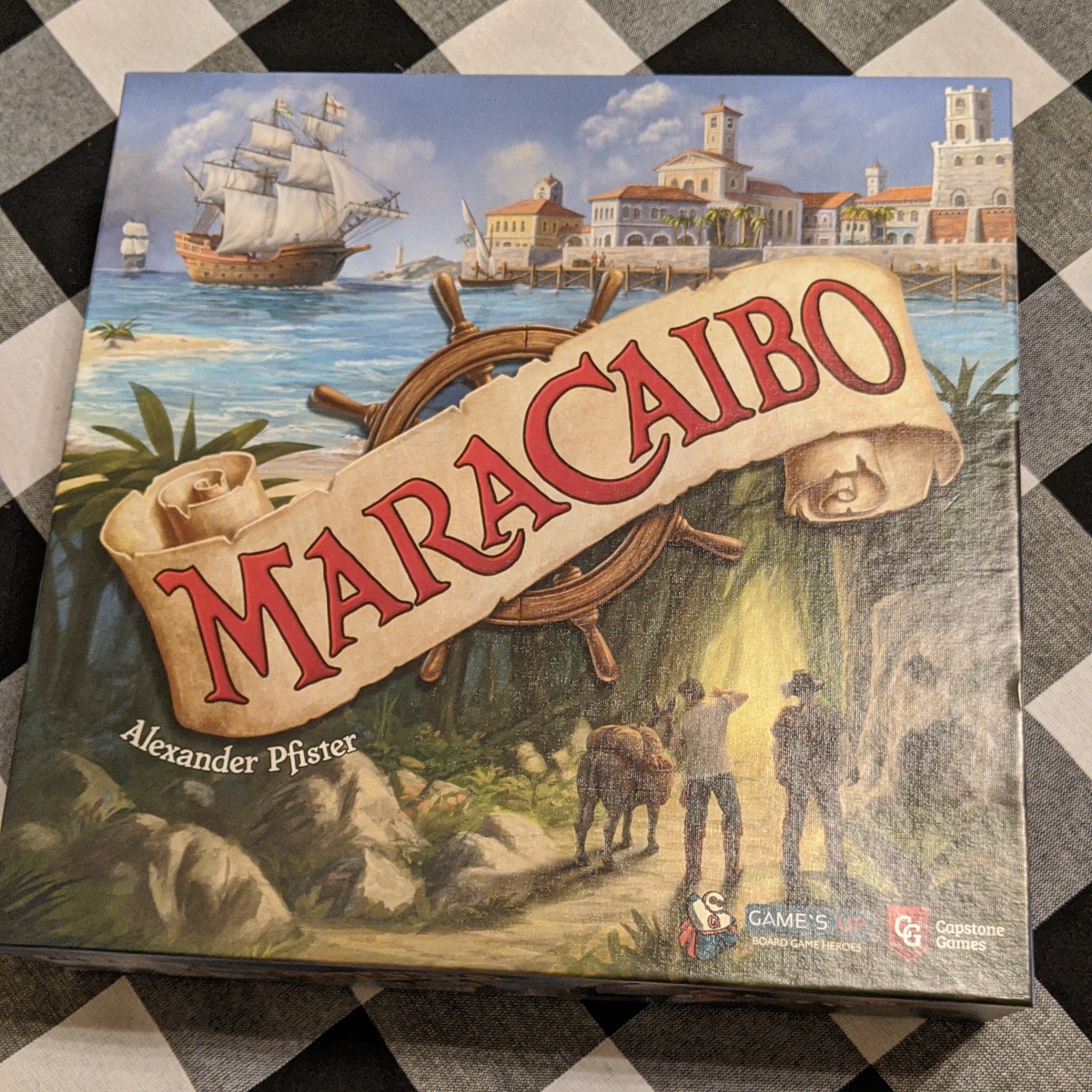

Maracaibo is an exploration Euro-style game set in the age of piracy in the 17th century Caribbean. Players assume the roles of ship captains assembling crews, delivering goods, and vying for influence of the European superpowers that control the area.

While at its core, gameplay consists of moving your ship, performing one or more actions, and refilling your hand of cards, the game offers a wide range of different things to do and strategies to employ, not dissimilar from most modern strategy games. The complexity lies in the sheer number of things you can do that constitutes taking an action. Each turn you can choose how far to sail your ship, between one and seven spaces. Once you’ve stopped, you take actions depending on where you’ve landed.

If you’re at a major port, you can deliver goods in exchange for unlocking extra actions or bonuses on your ship. Each major port also has a specific action you can take that ranges from participating in combat with one of the three main nations to advancing your crew’s progress with exploration on land. If you’ve stopped at one of the intermediate smaller islands, you have a generic pool of “village” actions you can choose from. Obtaining upgrades on your ship can even unlock additional things to do. Depending on how far you sailed this turn, you can take one, two, or even three of these village actions at a time.

Why not just move the maximum distance every turn, you ask? Well, that’s where Maracaibo draws a little inspiration from one of Pfister’s previous games, Great Western Trail. The sailing route in Maracaibo, much like GWT‘s westward trail, has a definite start point and end point. Once you make it to the final space on the track, you refresh the game and start again from the top. Where this game differs from GWT, however, is that once ANY player makes it to the end of the track, the round ends for everyone. Because of this, the game forces you to balance moving slowly, hitting as many ports as possible, with moving quick enough to travel as far as you can before someone inevitably pushes the game onward.

In my first time playing the game, I can’t help but feel a little conflicted about this mechanic. In theory it’s a fantastic way for the players to set their own pace, but in practice I’m constantly fearing a single salty player blazing through the game as fast as possible to the detriment of their own score as well as everyone else. The game takes place over only four rounds, and it’s very easy to get overwhelmed with starting a project only to realize that you may not have enough time for everything to come to fruition. But hey, I guess you can argue that’s a way for players to adopt a more adaptive playstyle and roll with the punches a bit.

It seems like in a typical game of Maracaibo, you will be spending a lot of your time managing your hand of cards with your village actions. Cards you keep in hand can be used for a number of things: as a specific trade good to deliver to a major port, an object to satisfy a quest, or simply as a crew member or associate that can give you an active or passive benefit. It’s this variability in card use that turns what seems like a straight-forward choice into something more nuanced. Do you save up money to buy an explorer to push your expedition deeper into the jungles of South America or do you forfeit the card to deliver sugar to port in exchange for ship upgrades? I found myself constantly needing to abandon certain plans in favor of others because the cards I was holding at any given time.

Maracaibo is a game that I really enjoyed and look forward to playing again. The learning curve for the rules isn’t the steepest among games I’ve played, but it’s definitely complex enough to possibly scare away anyone without reasonable experience with medium-heavy euro games. The game can look extremely daunting at first glance, but it uses a metric ton of iconography to explain concepts that become clear as you play. This is a game I will definitely try to come back to sooner rather than later because I don’t look forward to needing to re-learn it all from scratch.

Note: On top of all of these aspects of the game to keep track of, the game features a “campaign” that features unique board setups that can be played sequentially over several games as a loose story. My only play of this game as of yet did not utilize this method and instead used the traditional setup rules with a static board state.