Sidereal Confluence is a negotiation and trading game designed by TauCeti Deichmann and first published by WizKids Games in 2017. Thematically, players each play as one of nine distinct races of aliens working together to achieve The Confluence, an idealized society where technological advancements are shared throughout the galaxy. Everyone is working towards the same goal, but this is no cooperative game; everyone is vying to do it “more better” than each of their opponents. The rule book describes it as a game of “aggressive cooperation.”

A breakdown of the teach

At its core, gameplay revolves around engine-building, which is to say you are pulling pieces together that work well on their own, but work better together. Each race has a unique set of “converters” that turn input resources and produce an output of different resources. Unfortunately, typically a race does not start with enough resources of certain types to run all of their converters. This is where this game’s trading and negotiation comes in.

Each turn (or round, of which there are 6 across the length of the game) starts out with an intense trading phase. Almost everything is up for grabs: resources, ships that you use to bid on more cards, resource-generating planets, and even research teams that hold the future promise of unlocking new converters later on down the road. Even more, you can actually barter with your own unused converters, letting other players use them for a single turn before giving them back. All trades and promises made in this phase are binding, so if you say you’re going to hold up your end of the bargain in a later turn, you have to do it. Once trading is complete, players simultaneously run their converters to (hopefully) turn a profit.

Keeping with this game’s theme of “aggressive cooperation” any technologies that were developed during trading as the result of funding research teams are now shared with every other player. The player who initially developed the new converter gets points for doing so and also gets a half-turn jumpstart on using it, but by the start of the next turn everyone will have access to their race’s slightly-modified version of the same technology. These technologies can even be sacrificed to upgrade existing converters. By now you can probably see the depth of choice involved with building out your own.

Each turn rounds out with two phases of bidding, one for the colonization of new planets and another for more research teams. This is achieved via closed-fist auction using ships that may have been traded for or generated from converters. Once the bidding is done the game wraps back around to another phase of trading and after 6 turns resources and points are tallied to determine the most aggressive cooperator.

Race for the galaxy

Seems pretty straight-forward, right? What if I told you that each of the nine playable races has their own quirks that make them play radically different from one another?

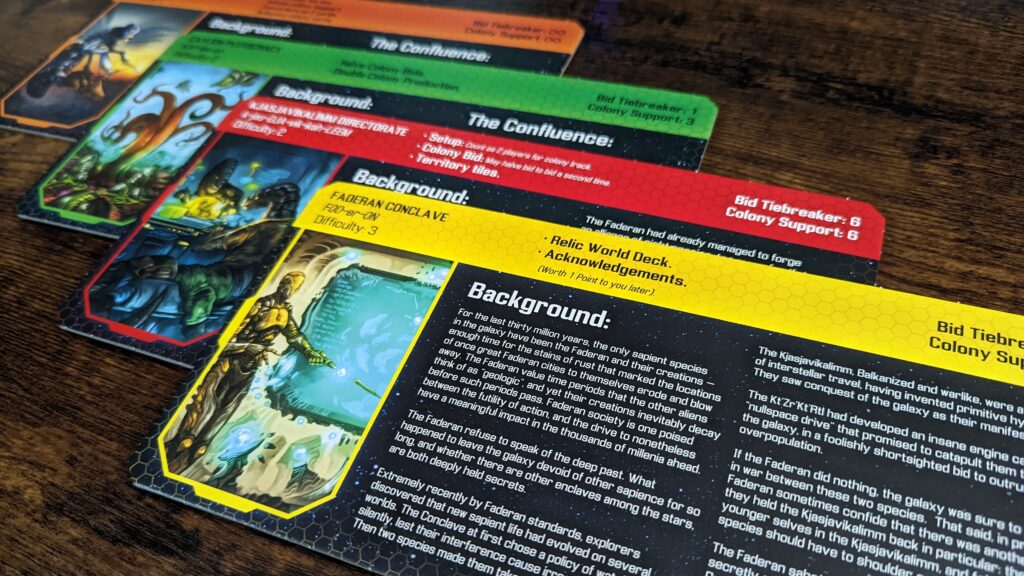

For my first time playing the game, the rules recommended the four least-complex races. The Kt’za’kt’rtl Adhocracy is a race of intergalactic space bees that have access to their own separate deck of colonies that nobody else can colonize as well as jumbo converts that span two cards each that can be upgraded half at a time.

The Caylion Plutocracy is a race of sentient plants that can make colonies double-produce at the expense of needing to pay double for settling them. These boosted colonies make excellent bargaining chips in the Trade phase.

The Kjasjavikalimm Directorate are a reptile-looking race that boast a powerful military that allows them to split their colony bid and secure two spots in line as well as special territory tiles that act as super-converters they can create by consuming colonies.

Lastly, I played as the Faderan Conclave, a race of mysterious robots that seem to have been running things from behind a curtain for millions of years. They are allowed to trade away “acknowledgements” that in-turn give them points whenever an acknowledged race develops new technology. They can also consume certain colonies to develop “relic worlds” that give powerful passive effects or a specialized converter. And there are still five other races I have yet to see in action!

So how does it feel?

At first glance all of the cards and cubes and tokens spread out across the table make Sidereal Confluence look extremely daunting. Even without the possibility of trading with other players, the sheer amount of choice involved with where you spend your resources is enough to lock some of the more indecisive players into endless thought. Luckily each of the races come with a player board that expounds upon some basic strategy, all of which I kindly ignored (to my detriment) on my first game.

I normally turn my nose up at negotiation games because they tend to live and die by the group you play them with. I think Sidereal Confluence confluence mitigates this problem in a couple different ways. Firstly, players who don’t make trades in this game will get absolutely nowhere fast. You’ll stare down at your desolate empire of technology and realize you can’t produce anything without getting rid of the things you don’t need for resources you do. It’s sink or swim and I think the game does a good job at kind of forcing you right into the drink.

The other way the game subverted my expectations when it came to trading and negotiating was in the sheer number of things you have at your disposal to offer up. Apart from the physical point tokens you get in various ways, pretty much everything else is fair game. Halfway into the game I realized that if I couldn’t get the resources to run a particular converter, I should be offering up that particular converter to someone who could use it. At least in that way I would be getting something for my troubles. It’s moments like this that I really fell in love with the game because it was teaching me to think differently. Not every relationship had to be contentious. Instead, I could foster a symbiotic relationship and raise the tide for all boats. I don’t think I’ve ever seen this kind of dynamic in a game before.

Wrapping up

The game plays from four players all the way up to an absurd 9 simultaneous players. At four, I was able to teach and play a full game in around two and a half hours with only a few quick glances back at the rule book for clarification. Most of the issues came with the interaction of the racial powers and were explained thoroughly-enough on the player reference boards. Scaling the game up to five or six players would probably work fine within 3 hours, depending on how crazy negotiations spin out, but I don’t know if I would be willing to do any more than that outside of a convention or special event scenario.

Call it a form of confirmation bias, but I think I tend to favor games I own and am able to sit down and learn in the comfort of my own home. It’s very rare that I put in the research and purchase a game that I absolutely loathe after the first play. I was terrified upon breaking open the box for the first time to read the rules that this seven-pound box chock-full of bits and bobs would never make it to the table due to its complexity. That it would be reserved for playing with only the most seasoned board game veterans among my friends. While I don’t think it’s going to make board game enthusiasts out of my friends who already don’t like strategy games, I do think it has much broader appeal than I initially gave it credit for.

Sidereal Confluence on BoardGameGeek